Introduction and Context#

In this new entry in the series “Product Management from the trenches,” I will focus on my first steps in prioritizing the initial actions to be taken by the teams, or as I like to call it, separating the wheat from the chaff, and starting to prioritize the CPO-level backlog of initiatives.

For those readers who find themselves reading this post without having read the rest of the entries in the series, apart from recommending that you read the series from the beginning, allow me to remind you a bit about the context. We are in a scale-up incumbent company in the industry with a reached product-market fit but where there was no practice of product management as such. This company was acquired by a private equity fund, and they brought in a CPO to professionalize how to launch initiatives that meet their customers’ needs.

The first thing I would like to highlight here is that prioritizing the set of initiatives at the CPO level is not the same as prioritizing a product backlog, although it can be done in a very similar way. At the CPO level, it is about selecting strategic opportunities, and this prioritization aims to build and strengthen our competitive advantages as an organization, which requires understanding the strategic positioning of the company, the competitive dynamics of the industry, and also taking it into account over various time horizons (think of the McKinsey’s Three Horizons framework).

I also mentioned in the previous entry that the origins of prioritization in this company were a weekly meeting where the company’s most expensive resources would gather to indicate what functionalities and tasks were going to be carried out, with the consequent lack of empowerment of the teams and delays derived from the executives’ dependency to resolve doubts.

Strategic Prioritization: Beyond the Traditional Roadmap#

With this context in mind, my intention for today’s post is to play a bit with the roadmap-nova (for the younger ones, I’m referring to a series of board games from the 90s that taught various disciplines: alfanova for pottery, volcanova for understanding how volcanoes work, serigraphic-nova for learning screen printing, choconova for making chocolate figures, and a long etcetera. Here is a link for those who are nostalgic or wish to delve deeper), so let’s design our own backlog.

There are many tools available in the market for creating and managing backlogs: Trello, Jira, Youtrack, productboard, dragonboat, etc., and they are excellent tools that perform their functions well, and I have nothing against them. However, I will focus here on what components each backlog entry should have, which serve different purposes but allow us to have a good understanding of the initiative, what it serves for, its impact, which team is working on it, and how it fits within the company’s strategy.

On the other hand, in my experience, I’ve learned that it’s easy to get excited about the implementation of tools, myself included, because obviously, it has a productivity boost, quick deployment, and we often overlook the cost that this entails. Specifically, no one had a product management mindset in my case, so I couldn’t go from 0 to 100 quickly, I had to build that mindset and practice of product management gradually. Thus, my approach in this context was to tackle the situation from first principles, to avoid getting into a process of setting requirements, searching for tool providers, speaking with them, acquiring the tool, onboarding and configuring it, training the corresponding teams, etc.

And here I’d like to pause briefly to comment on three implicit concepts in the previous paragraph, which might not be so evident, but can help you if you find yourself in a quagmire of such caliber.

The first concept is “the factory is the product”, as a CPO, one of your many missions is to “order the house,” to establish the set of processes and dynamics within the organization so that the product comes out well from the factory, meaning you don’t have to worry so much about the fine-grain detail of the last byte of the last feature, but you do need to ensure that the entire product lifecycle at the organizational level functions well, what I mean is that attention must be paid to the process of making the product and not just the product outcome (which also matters but that you leave to your teams).

Mind you, I’m not saying that the latter is not important, only that in my experience the outcome will depend on many other variables that are probably out of control. This last concept I learned from Jaime Rodríguez de Santiago in his Kaizen podcast, and I couldn’t agree more with him, the result of an action does not determine if the decision was good or bad, but the process of making the decision is what makes a decision good or bad, hence why I carry the concept of “the factory is the product.” Incidentally, this phrase is attributed to Taiichi Ohno, a Japanese industrial engineer and one of the creators of the Toyota production system, also known as Lean Manufacturing.

The second concept I wanted to mention is the zone of proximal development or zone of proximal development, which essentially means that when two people with vastly different levels of understanding about a particular topic, it will be difficult for them to have a fruitful conversation about it, and the learner will need some supervision and support to fill that knowledge gap, which is exactly what happened to me in this company, no one knew what a product manager did, so by establishing an enriched backlog I was able to train their minds towards this mindset.

The third and last concept I’d like to discuss is an aspect I learned in the master’s degree in coaching and mentoring at UNIR, and it’s that, in a way, thoughts, behaviors, and emotions are connected, I won’t dwell much on this because there is plenty of literature, but basically when you are in a transformation process you can’t just wave a magic wand and change people’s minds to think differently, in this case, I wanted to change their thoughts by forcing a change in their behavior, in this case when filling out the backlog information, I was reusing this prioritization ceremony for my purpose.

Note the interdisciplinarity applied throughout this process, we have taken concepts from various disciplines and brought them into product management, which in my understanding is very close to what is a complex problem (CPSer approves).

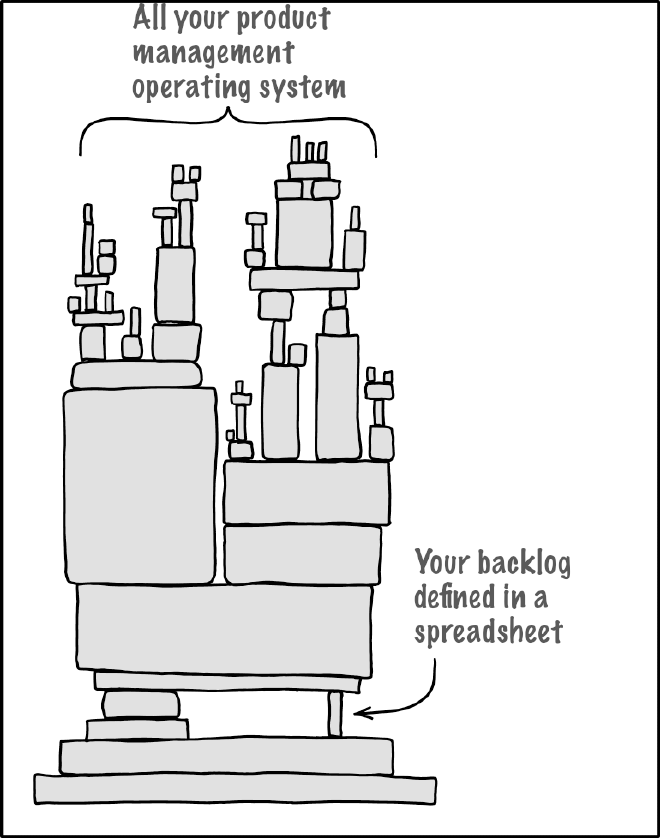

In conclusion, you don’t need the latest tool to have an optimized and effective backlog, in my case, I did it with Google Sheets, which was the tool they were already using and what I dedicated myself to was enriching it. This reminds me of this meme:

Designing an Effective Backlog: Key Components and Strategies#

Returning to the idea of how I design my own backlog, or put another way, what elements are interesting for each backlog entry, I understand each entry as a brief description of the initiative and an identifier for it.

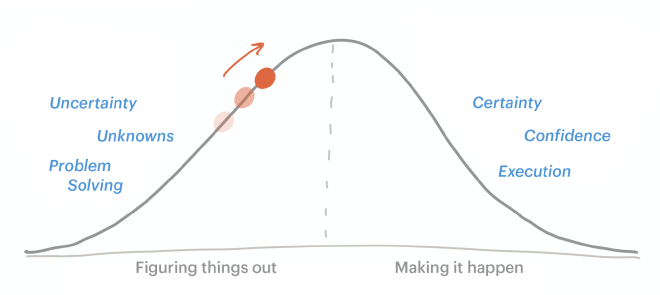

When it comes to prioritizing, obviously a very important aspect is the prioritization mechanism. There are many, but I prefer to use a modified ICE model. The fundamental idea behind this mini-framework is to understand the value or impact that the initiative in question will have relative to the effort it requires. Obviously, you will want to tackle initiatives that provide the greatest value with the least effort first, and then what you do is adjust the priority by introducing a level of confidence about your prediction, which in my case, this confidence level is established based on the level of definition of the initiative, directly correlating with the level of uncertainty of the same, thus for me the greater the level of definition, the better understanding of what I need to do, the greater confidence about what I need to do. This concept is well illustrated with the Basecamp hill chart, you can find the link here.

In my case, this level of certainty is defined by various events or situations:

- Sometimes I had inherited initiatives where the POs had already written the user stories, but they had been deprioritized, so there was a clear understanding of what needed to be done, ergo little uncertainty.

- If the UX Research team had passed through this initiative and it came based on needs detected in customers, then this gives me certain guarantees of the need.

- If there was a document of what I call an inception, which is somewhat my definition of a product requirement document or PRD, in another entry I will talk about the template I try to have for this definition of the initiative or functionality.

- If there was a commitment with a client (a contract or payment).

- If it was a compliance issue (meeting regulations because there was going to be an audit, for example).

Each of these situations is a parameter to fill in the backlog, and each modifies the value versus effort ratio downwards according to the level of uncertainty. Let me give you an example to make it clear, imagine we have Initiative A, which after having a conversation we decide contributes a value of size L shirt (assuming we only have five levels, so L would be 3 in value), similarly we define that the effort is somewhat medium, size M shirt (which in value would be a 2), this gives us a provisional prioritization of 3/2 = 1.5, then now we will make the correction, are the user stories written, has UX passed through there or do I have a document of inception? If no, I multiply by 80%, ergo I am lowering the priority, we go to the next event, it’s something that is a compliance issue, if yes then I multiply by 100% because it is almost mandatory to have it so I have to give it priority, in total if we multiply all the values we get that we have a priority of 1.5x0.8x1 = 1.2. In the end, it’s about creating a trust model based on your dimensions of uncertainty.

In any case, a new disclaimer, here it’s not about getting the number right in the framework, first because humans are terrible at measuring in absolute terms, but rather you try to relativize with the rest of the initiatives, it’s about fostering a conversation based on the four risks of product management: value, usability, feasibility, and profitability (these concepts can be seen in Marty Cagan’s book Inspired).

The second part of enrichment is the part of categorization or taxonomy, this part seeks to have a way to group initiatives, for several reasons:

- you’re curating and standardizing information to then

- build a series of dashboards on this backlog that will allow us to understand where teams are putting their efforts and by extension your strategic focus, I like to say that these dashboards will be your product compass.

- you’re elevating the conversation beyond the initiative and making people think at a different level of abstraction on a more strategic plane.

These categorizations for me include at least:

- Product the initiative refers to.

- Category of the initiative can refer to a module of a product, a particular problem within your products, etc.

- Client, if you’re in a B2B enterprise business and your clients have a lot of negotiating power there might be exclusive initiatives for clients.

- Strategic Theme, within the strategic initiatives of your portfolio roadmap where the initiative in question would be located, this is a mutually exclusive list, if you can’t place it in any strategic theme you probably shouldn’t be doing this initiative.

- Closely related to the previous one would be the objective that the initiative pursues: improving UX, customer engagement, increasing share of wallet, capturing new customers, etc.

- The last categorization I like to add is the stakeholder, understanding if there is a person who is the source of this initiative, for example, if it’s an initiative you’re doing for the CRO or CMO, this is important to also know who to turn to in case of any doubts.

The third part of the enrichment has more to do with the delivery, but I find it more relevant when generating artifacts and mechanisms to be able to debate with the board the implications of including new initiatives, and again to elevate the conversation to a higher level of abstraction:

- This component could have been added in the previous phase, but I included it here because it has more to do with the capacity of the teams, this additional category is to distinguish whether the initiative is a type: 1) Functionality, 2) Operational task, or 3) Resolving a bug. And why am I interested in categorizing this? because when I build the dashboards and see what the teams are dedicating themselves to, I can understand the bandwidth I

Fundamentals and Key Concepts for Success in Product Management#

There’s one aspect I’ve deliberately left out of this article, and that is that obviously all this enrichment and decision-making must be aligned with the roadmap. I haven’t done so, firstly because of the context in which it happened, I began to enrich the context of the backlog because one thing we must keep in mind is that you can’t stop a company to make your decision, instead, I had to build that product mindset without stopping the machines so I had to make small changes that would take me in that direction, secondly because there was obviously already inertia and commitments which made this mechanism a feedback to also build my strategic roadmap and thirdly because product making is not a linear process, normally when we talk about these things in The Hero Camp classes they are usually described in a sequential process of three parts: strategy, discovery, and delivery, but the reality is that it is not linear and all these processes feed back into each other and some make you change your strategy, others your functionalities, etc. Check out Nacho Bassino’s book, Product Direction, which explains this very well.

This approach also differs slightly from my more “pure” product mindset, so to speak, in that it is very focused on the initiative rather than the outcome. For me, the difference of a good product team is that it commits to the outcome and it doesn’t matter how many initiatives you undertake to achieve that result because the team has the necessary empowerment to make those decisions about which initiatives to tackle, but again here context rules, in this company the level of maturity of the discipline, as well as the understanding of the organization did not allow in my humble opinion to follow this type of approach.

The ultimate goal is to fail fast and cheap, adjusting your learning rate to put in front of your customer those solutions to their problems that provide value and for which they are willing to pay. The faster you learn, the more opportunities you have to evolve your product and thus the greater capacity you will have to tackle the challenges that arise.

In this entry, I am aware that I have not talked about how these initiatives reach the backlog, this is part of what I call the product operating system and I will discuss it in future entries.

Conclusion: Keys to Improving Decision-Making and Backlog Strategies#

In summary, the elements described in this entry: prioritization, categorization, and delivery, would be all those that I would seek to have in an enriched backlog that would allow us all to make better decisions without having to involve the most expensive resources of the organization. It will help us elevate the conversation to a more strategic level and also establish a common language when addressing the prioritization of initiatives, and by extension giving greater empowerment to the teams to decide what is done first and what is done next. Additionally, by curating the data, we will be able to build a series of dashboards that will allow us to steer the ship to safe harbor but I will talk about this in other articles too.

I hope you enjoyed this entry, how do you enrich your backlogs? What tools do you use? How do you build your product compass? Write to me to tell me how you would improve this approach, would you have done the same?